Cambeo had been running for approximately seven years, they had been a sales and marketing focused company building features into their web platform as customers requested them. This led them to have a Frankenstein of a product, with unrelated features patched together into a system that was unintuitive at best, and flat out unusable at worst.

An example of this happened as I was being onboarded to the company. A month or so before I started, one of the sales people was trying to close a sale when they were told, "We need it to have an inventory management system." Being a

As the company was shifting from this "build first, ask questions later" mentality, they hired their first designer. His role was to begin the process of defining a new design language to unify the many areas of the platform. Working with one of the best iOS developers in the area, they created beautiful prototypes with fluid animations and all the bells and whistles. Everyone who saw it was blown away at it's awesomeness, but it fell short in one area... it wasn't usable. Simply put, it was too complex for a store manager, who was our main target, to understand and get value from.

When I was brought on to the team, Cambeo was restructuring the way they worked. Focused on reinforcing the core of the platform, we set to work on understanding and defining what Cambeo did well and how we fit into the market.

As part of this effort, my role was to help define the goals and direction of the product, and implement the vision for the product in a way that was usable for our target audience. In order to accomplish this I first looked at how we might implement the UX process to help guide our discovery. Specifically, since we didn't have the resources of a full design oriented team (I was the only designer at this point) I looked at what parts we needed to learn what we needed and delivery quickly.

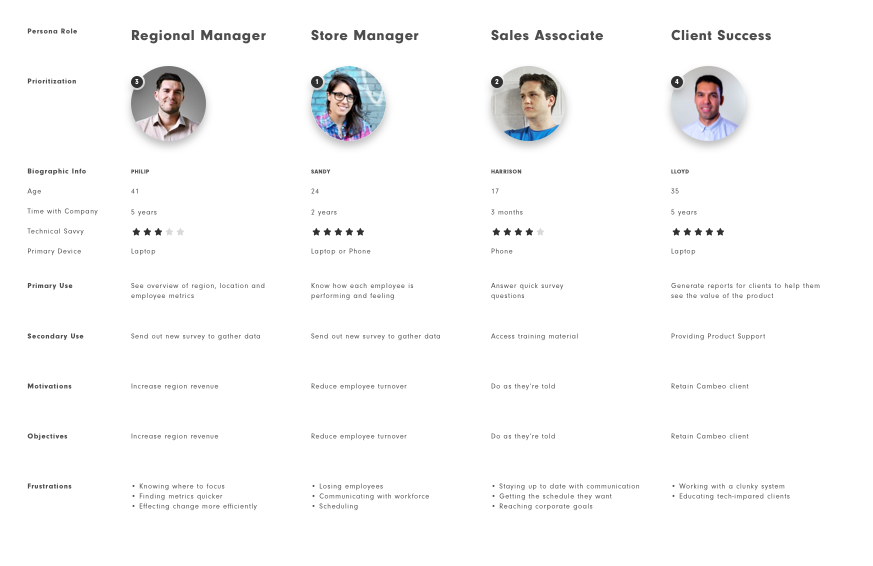

Understanding who our users are and how they think and work is vital to any good product. In order to learn enough about our target audience to get started, I first relied on the seven years of knowledge that the members of the team had gained. Starting with the ones closest to the source, I held meetings with our lead client support representative to discuss how our customers were currently using our product. From these meetings, I was able to get a closer look at what our users were trying to do with the product, the frustrations they had, and the ways they were navigating around the features/ui to accomplish their goals. I also realized the scope of the project as there were a lot of issues that needed addressing, from simple UI changes to rethinking the entire flow of major sections of the web app.

I was also able to sit in on support and training calls with customers. This allowed me to hear first hand many of the issues that they were facing, and also the level of urgency of some of these frustrations. We learned from these sessions that while people in different positions within a company look at problems in different ways, offering different solutions and methods for addressing these problems, they were mostly talking about the same issues with the same desired outcomes.

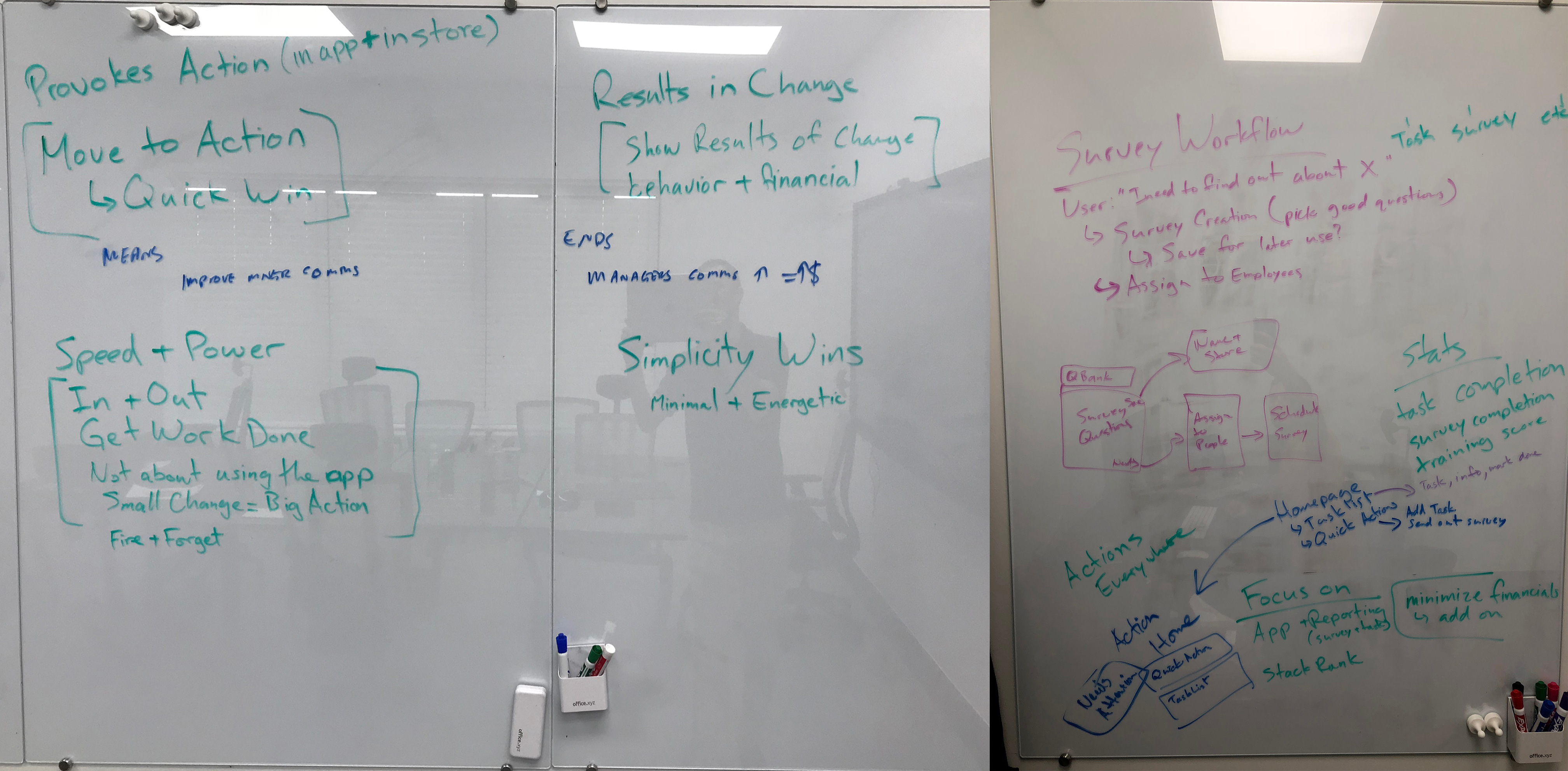

In our interviews, we had the opportunity to bring in a store manager who was one of the most well known in the area. She was confident, well respected, and very successful. As we asked questions, and listened to her story, we noticed certain patterns that she would do in each of her successes. Her success came down to two key findings:

We also discovered in these interviews and meetings that while there were high expectations for performance, often times there simply weren't the tools to ensure success. Issues came up where employees simply didn't know what was going on, or where they weren't getting the resources to be knowledgable enough about the products they were selling to be effective. Skills were unrefined and training was almost non-existent. As a result, potentially good people were leaving or getting fired, and many companies were struggling to maintain a properly staffed store.

These findings were confirmed by other interviews with people with prior management experience in the retail space. In these conversations, we discovered that managers too were under similar pressures, needing to perform without the support necessary to do so. Often store managers were required to work 60-80 hour weeks in order to accomplish the goals set by corporate, but corporate often was unwilling to provide resources or tools to make things easier. Managers needed tools in their hands, and it was common place to work around corporate guidelines to secure them.

Prior to this point, sales efforts were focused on convincing the top corporate people to implement Cambeo in their organizations. While this worked in some situations, specifically in organizations that were smaller and locally owned, larger organizations and big brand names took up to several years to convert. On top of this, many front-line employees (store managers and associates) resisted any initiative announced by corporate, stating the disconnect between the suits in the office and the people on the ground.

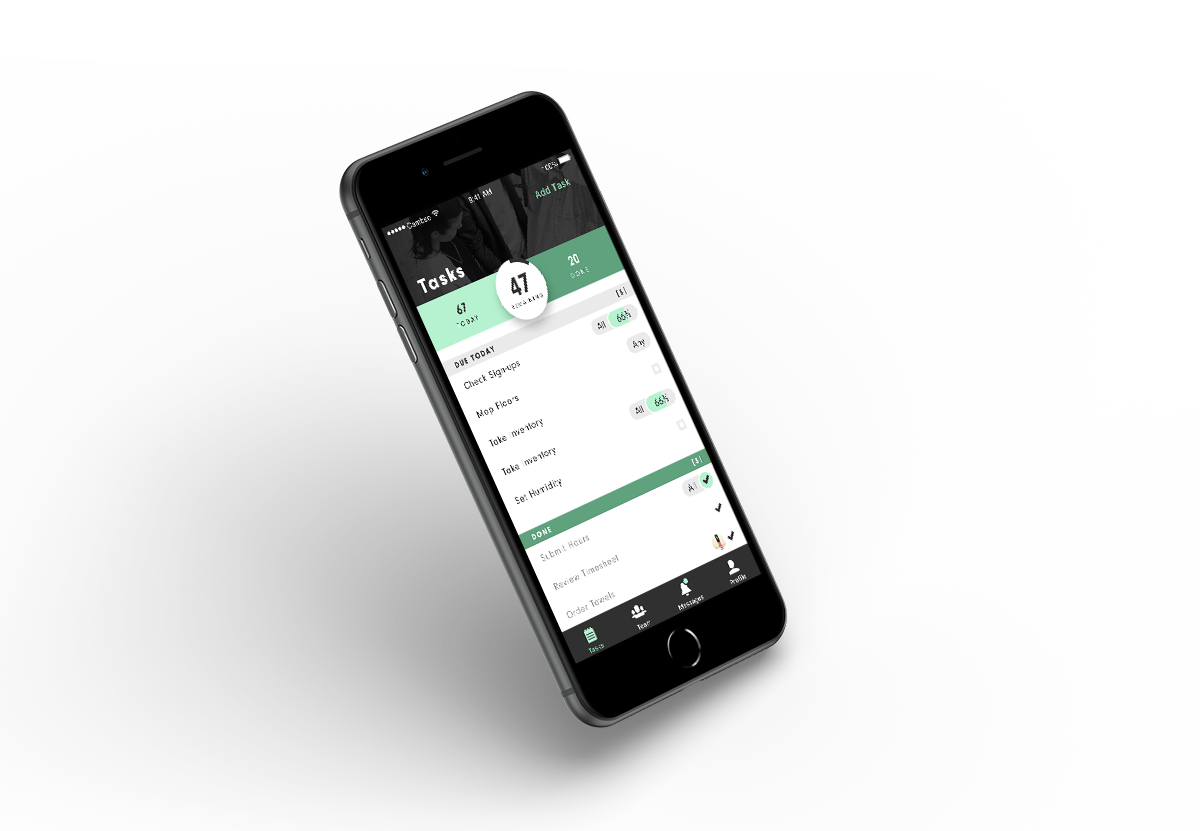

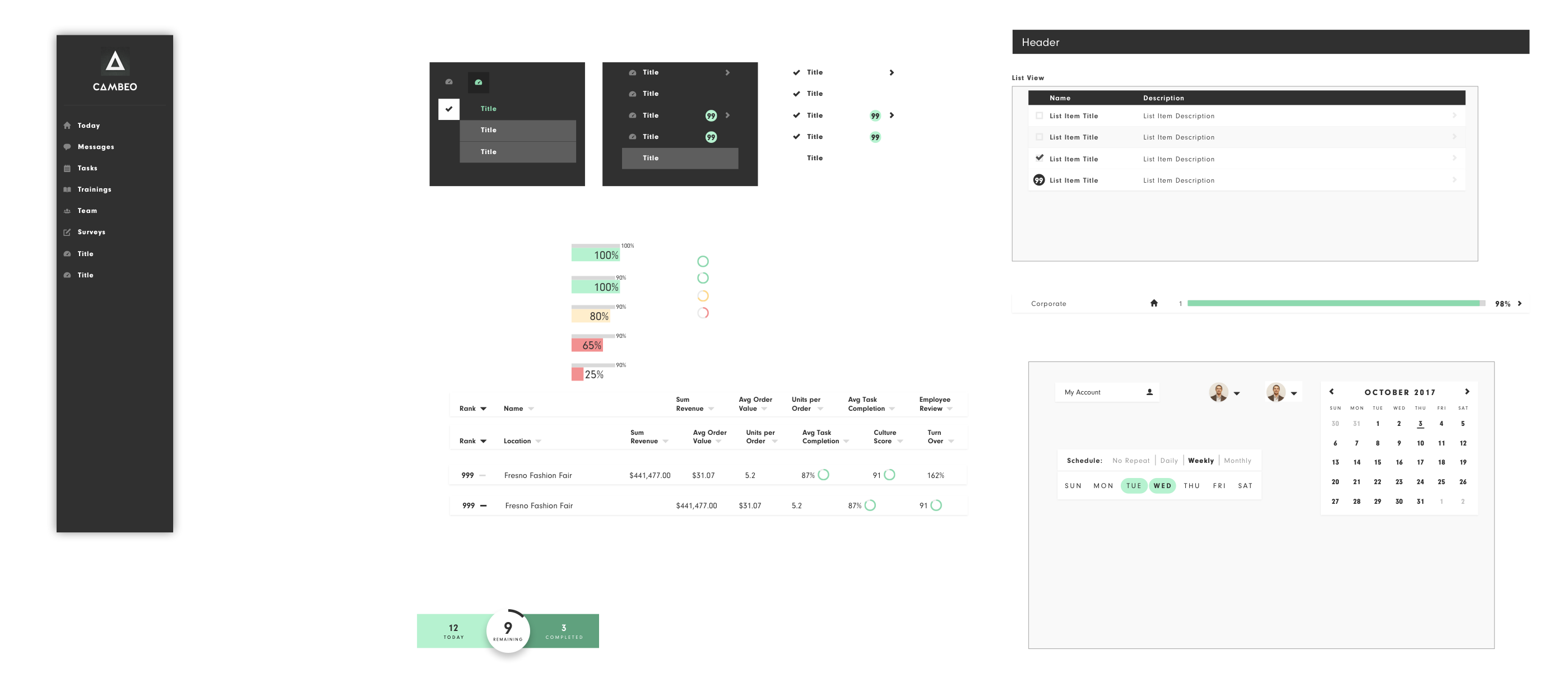

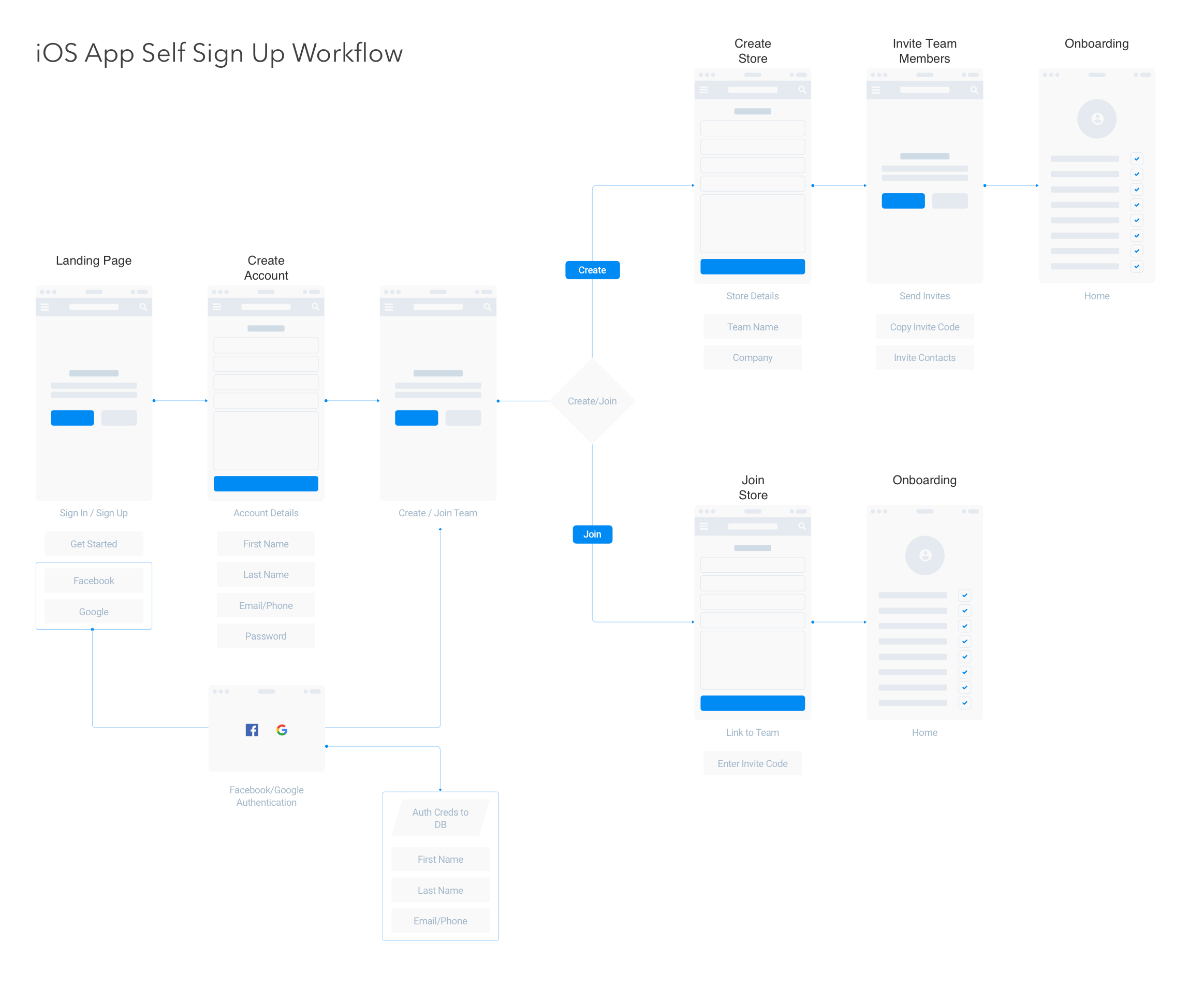

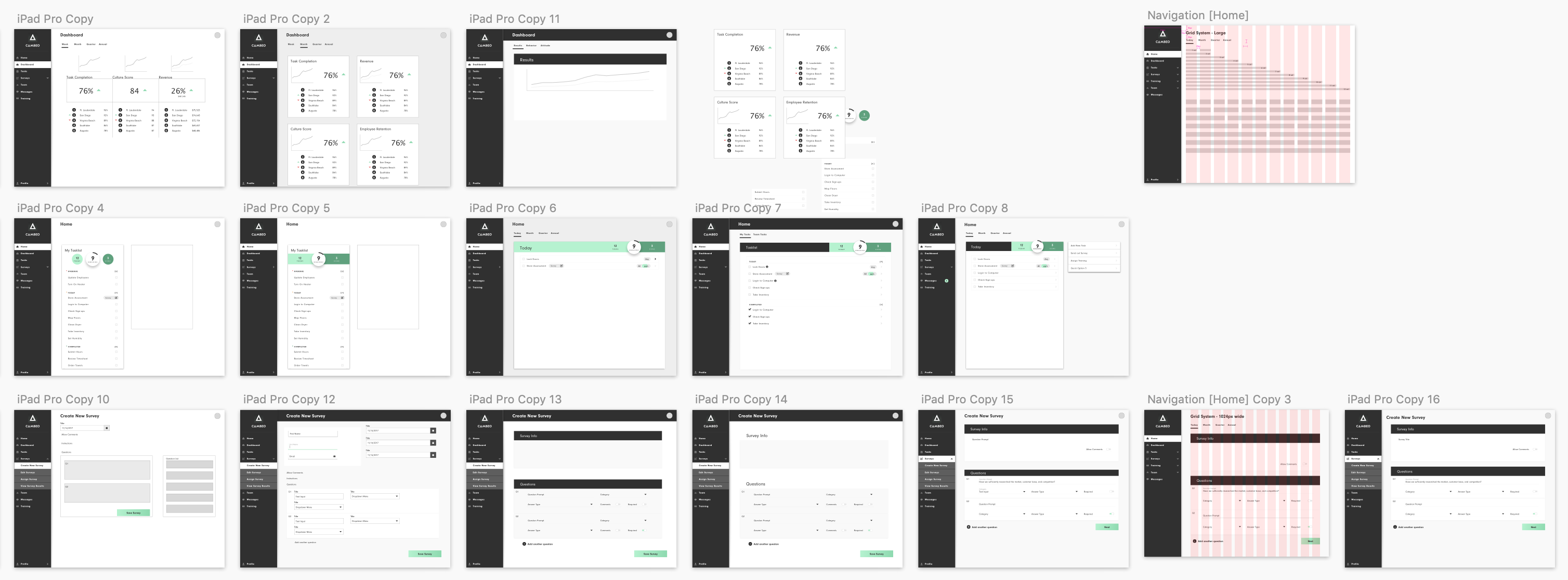

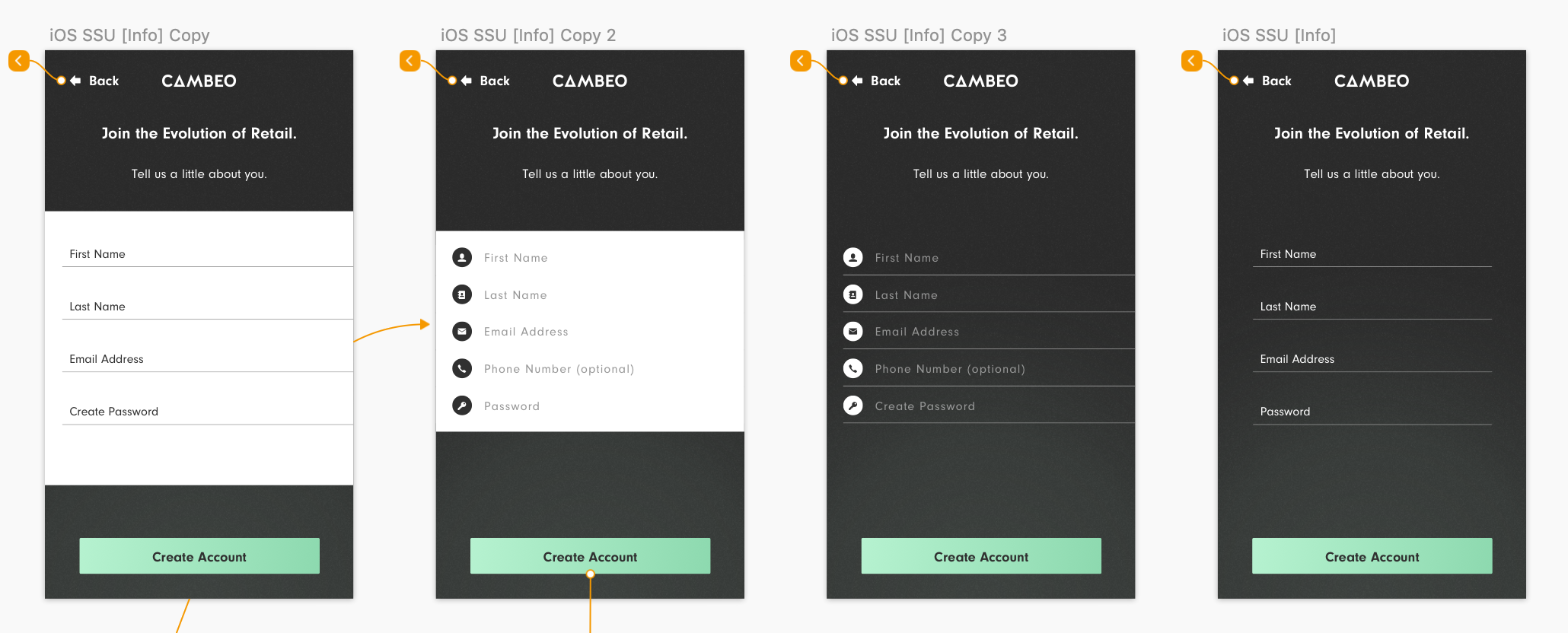

Armed with this knowledge, and the need to see adoption, we pivoted the product to focus on front-line needs and took a more grass-roots approach to marketing. We decided that in order to make our product more accessible to these workers, we would convert the primary features into a mobile app that could be used on the floor. This also allowed us to start with a clean slate and focus on delivering a simple and intuitive product without the clutter of "legacy" features such as inventory management. While we were starting development on the mobile app, we decided to also bring the web app's design up to a similar standard of quality, so the redesign work for that also began.

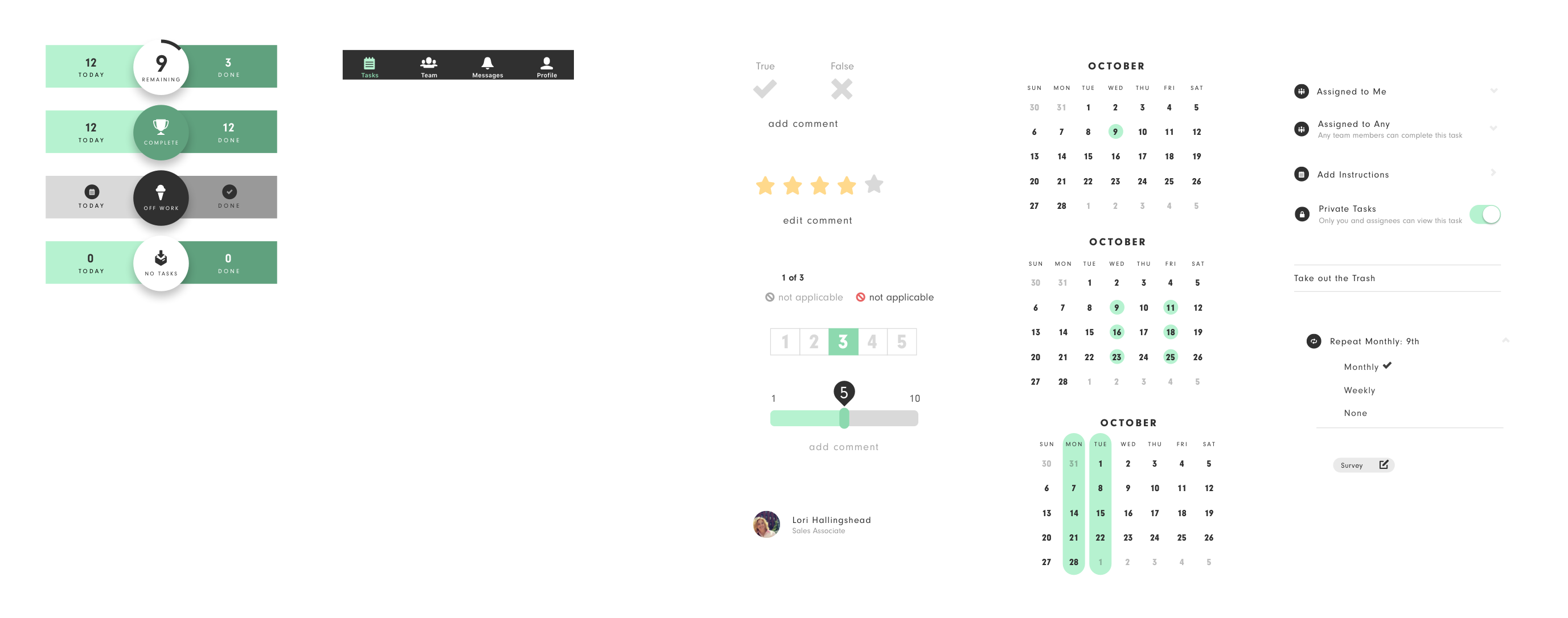

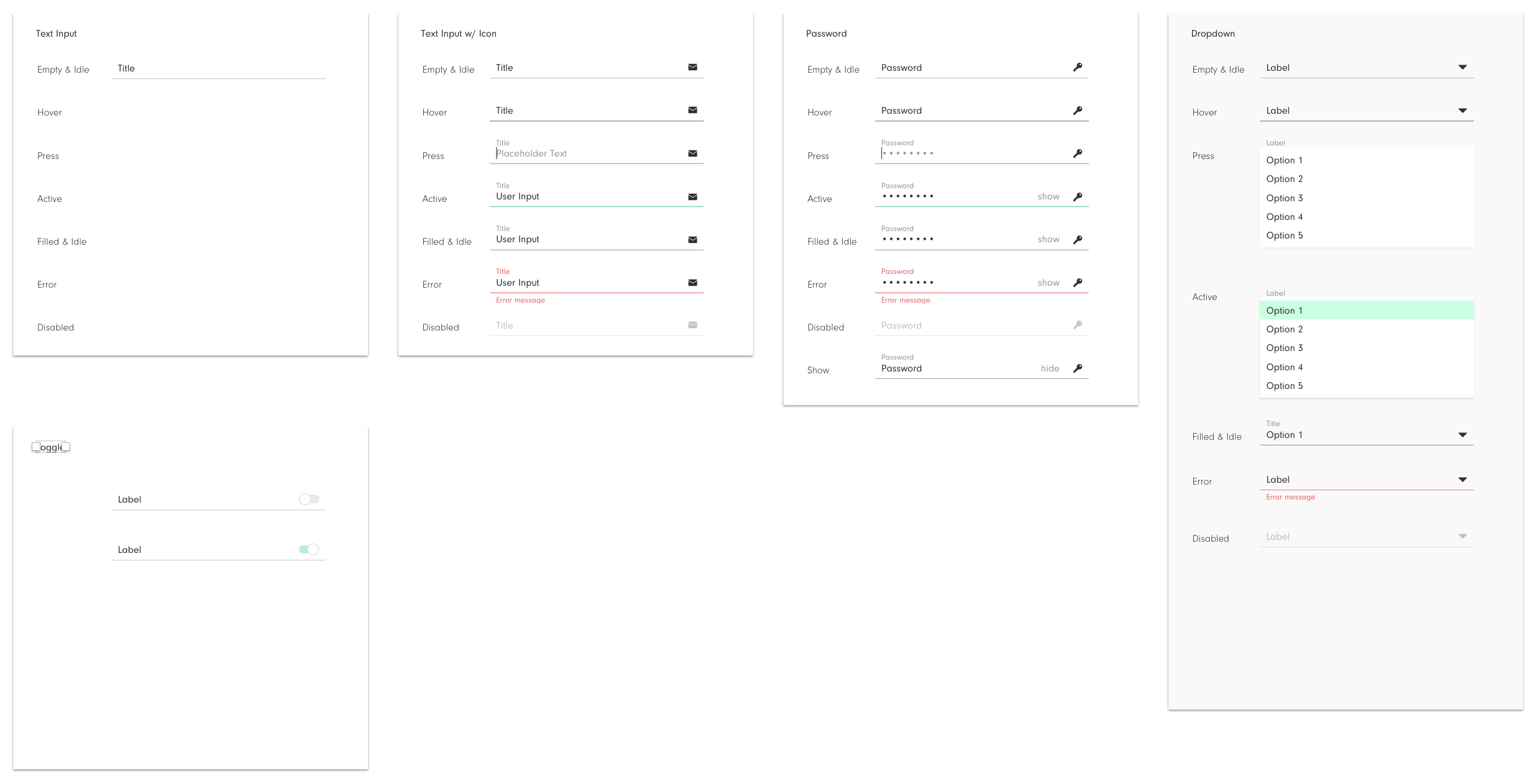

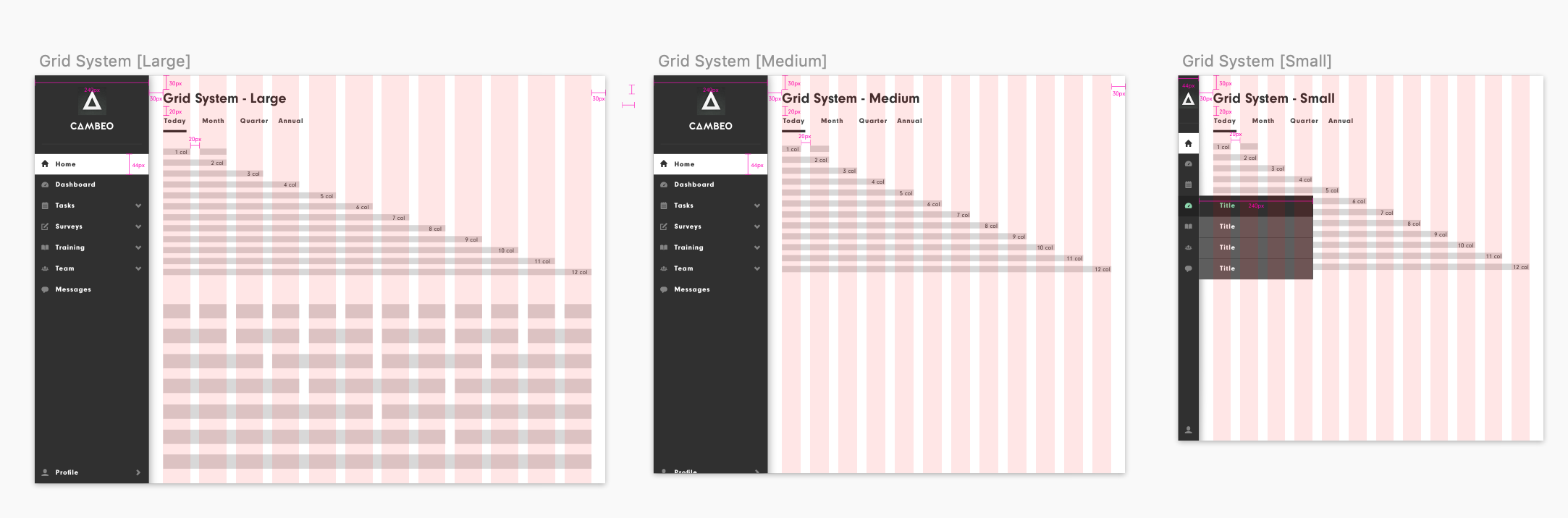

As part of this new direction, I set to work on designing the basic elements that would be used to create components: text fields, inputs, toggles, buttons, etc. Doing so allowed me to quickly move ideas from wireframes and flow charts to high fidelity prototypes. This greatly reduced the time from initial concepts to delivery of tested designs to developers for implementation. As we added designers for different projects, this also helped keep the continuity across the whole platform. It also allowed more junior designers to contribute to the product quickly and efficiently as they could focus on the layout and hierarchy of the design rather than the specific details of each component.

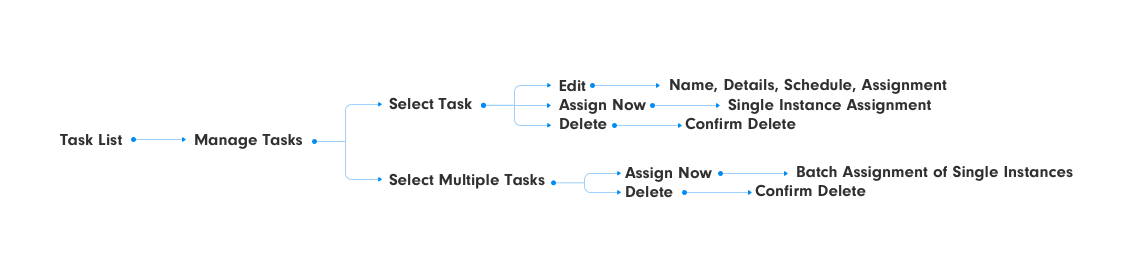

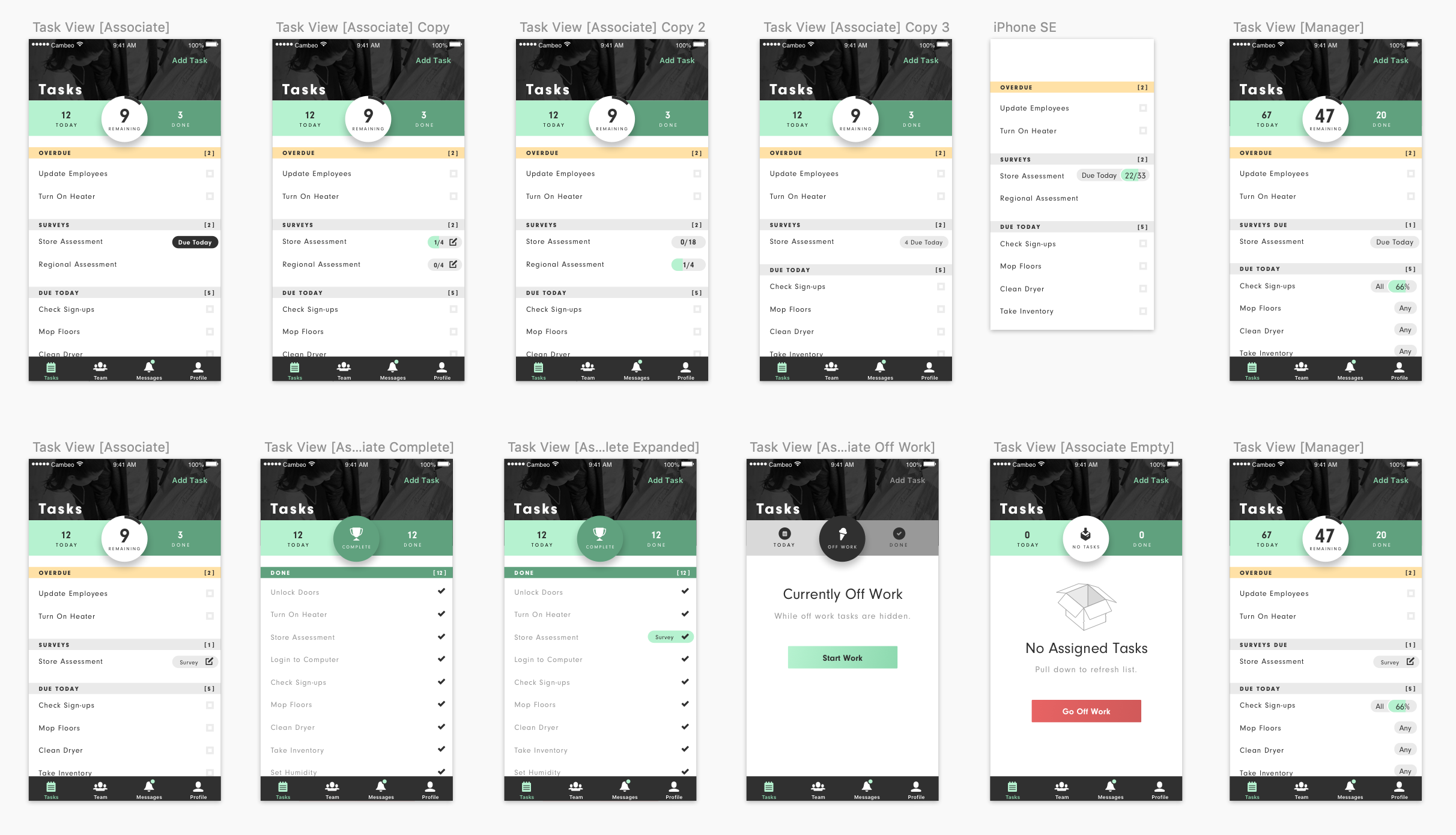

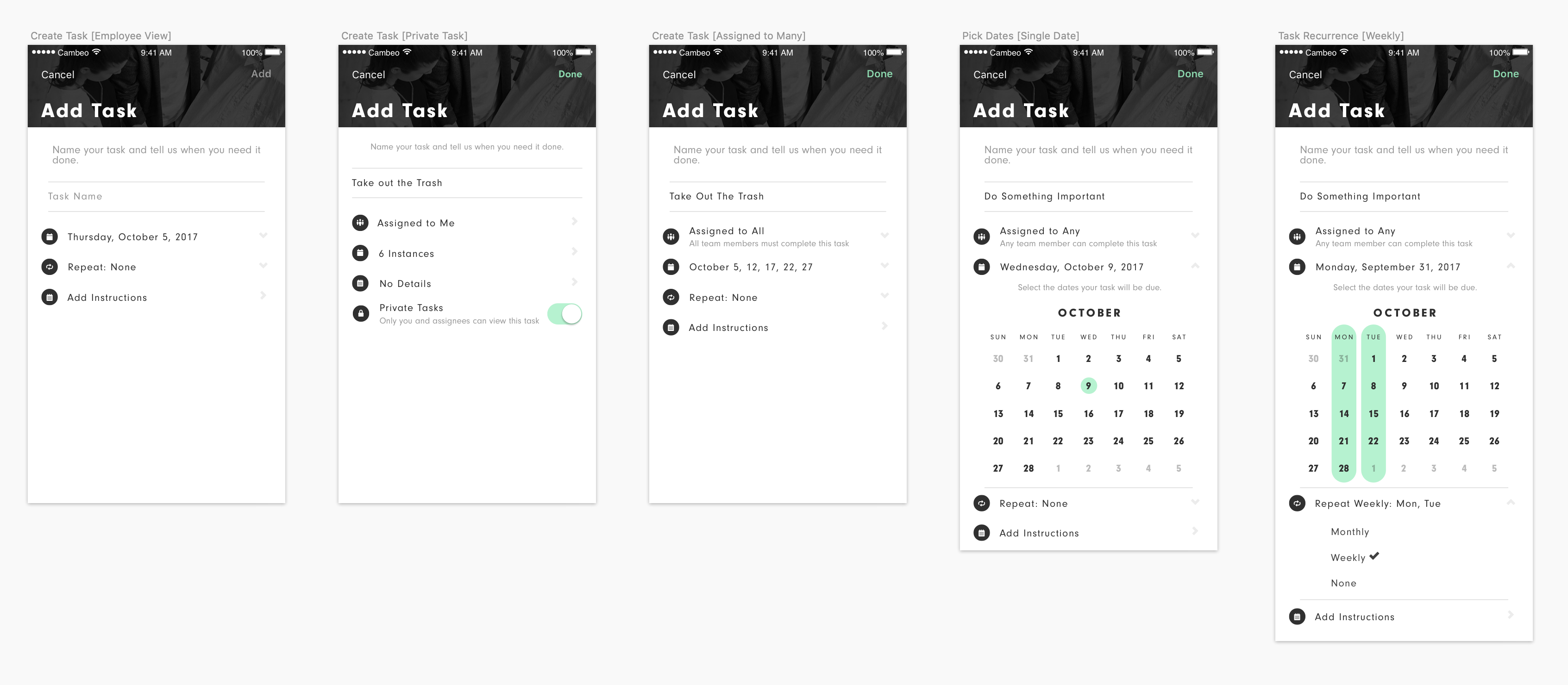

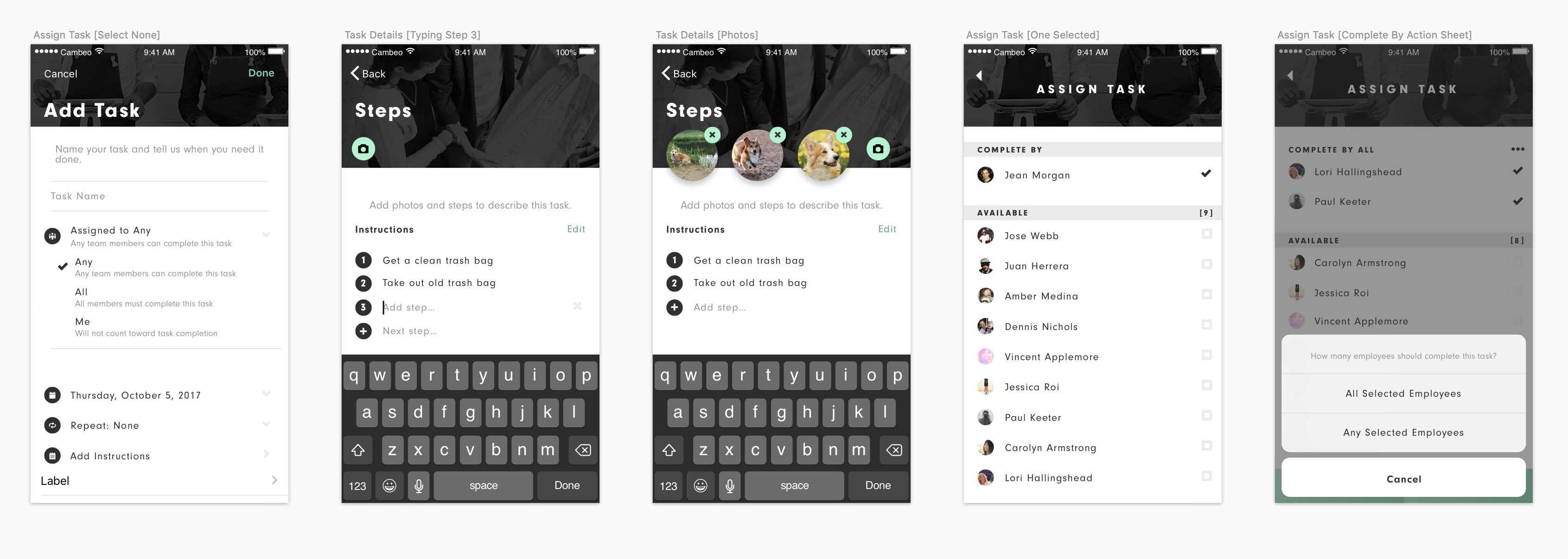

In collaboration with client success, management, and the rest of the product team, I tackled the major task of designing the core of the mobile app. What would it do, how would it do it. There were key goals provided by my product manager, and a base prototype done by the previous designer, which I used as a starting point for my work. After stripping out any unnecessary elements and features from the old prototype, and then applying best practice usability standards to what we decided to keep, I set out to define how the app was to function.

We stayed true to the fail fast, fail often approach as we iterated through prototypes, testing each design as soon as we could to validate the usability and usefulness of each version. In order to speed up the process even more, we tested initially with client success representatives and people in the vicinity who had retail experience. Once we discovered and iterated on the most universal and egregious issues, we would go further out into the community to test with current retail staff. These guerrilla tests allowed us to maintain focus on the people we were designing and building for and helped prevent us from straying from our primary goal, which was to help the front-line worker.

Through our testing and research, we came across a potential issue where some store managers were hesitant to allow their employees to have their phones on them while working, as they were afraid it would be a distraction. To help address these concerns, we set targets to limit the time required for use, so that any task performed within the app would be limited to short interactions.

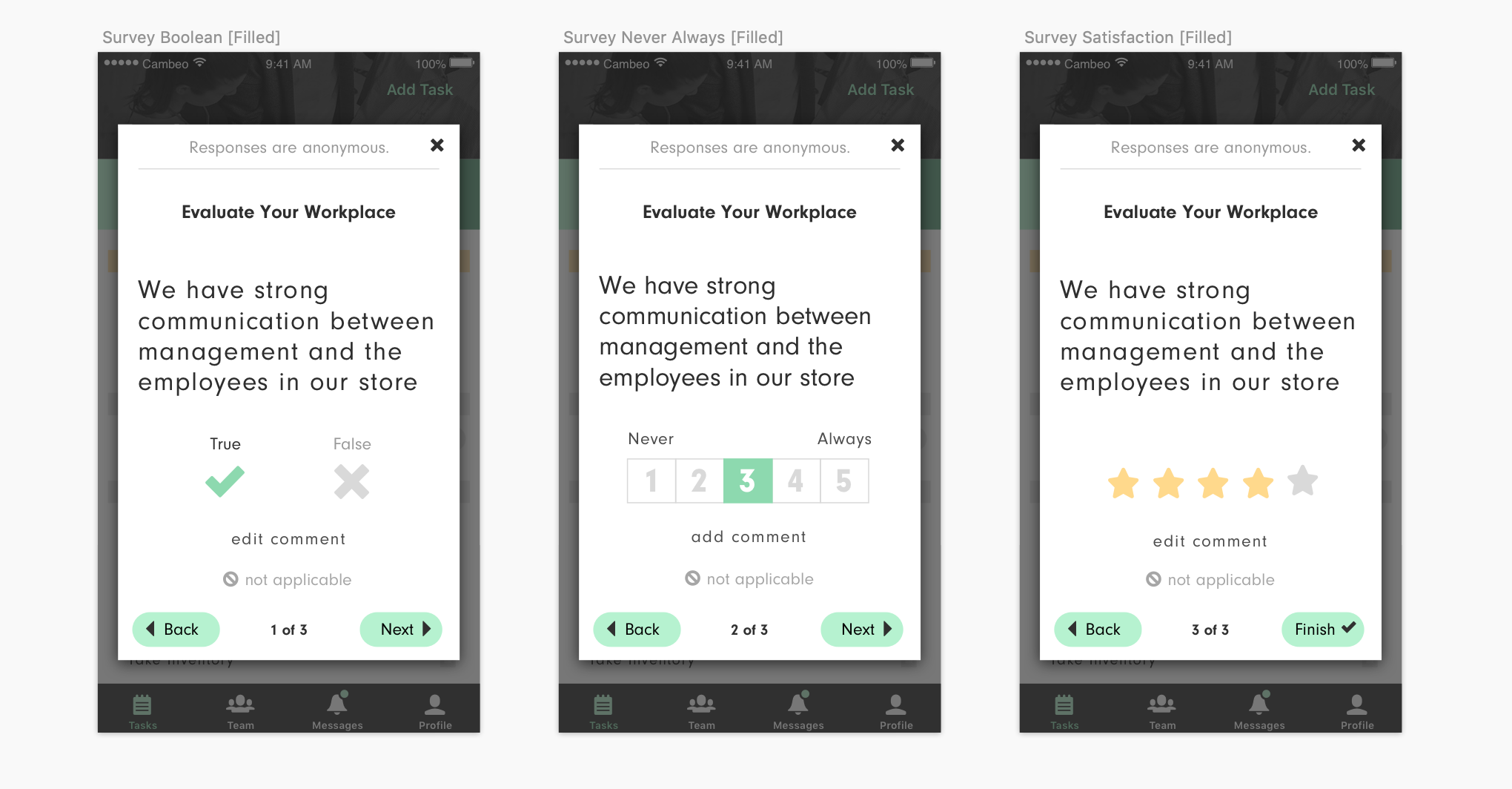

This affected almost everything we did. As we worked toward launching our initial release we applied this target to all of our core features, including task management and employee surveys. This created an interesting challenge for employee surveys in particular, since traditionally these evaluations often took 30 minutes to an hour to complete. We devised a system that would allow the survey to be distributed in "chunks" so that each day employees would receive a small set of questions from the survey that they were assigned to complete. This allowed the worker to give feedback to their managers over the course of a few days without taking significant time out of their day to complete the survey.

As we implemented these ideas and tested them with store managers, we started to see a change in the enthusiasm and excitement for our product. While many managers were already expressing the desire for tools, we started to see them ask about how to download and use our product, without our prompting.

By understanding what we needed to accomplish, and applying the UX Process in a way suitable to our team, we were able to quickly adapt and take an old and clunky system, and give it new life. We saw excitement that hadn't been there before, we were reaching people where they worked, and we provided the tools and resources that they were looking for.

But the process never stops. As we released our initial version, we discovered more areas where we could improve, and even more opportunities to create value for our users. We explored ways in which we could introduce machine learning to help pre-populate data, or ways to analyze the data that we collected to give smart recommendations to managers. The challenges were endless, but as we learned, it only takes small steps to make a big impact.